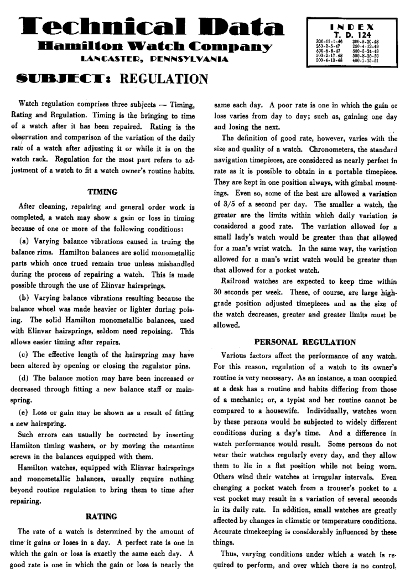

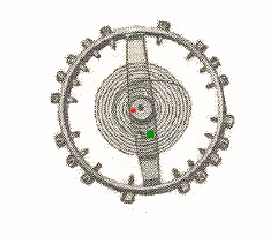

Position adjustment refers to the mechanical design of the balance wheel and the hairspring. The little weights on the balance wheel are an important part of that adjustment. It is done to maintain approximately the same rate of balance wheel oscillation, regardless of which of the specified positions the watch is in. The 6 positions are: (1) dial up, (2) dial down, (3) stem up, (4) stem at 9 o'clock and (5) stem at 3 o'clock, (6) stem down at the 6 o'clock.

It's the positional adjustment and the temperature adjustment that sets this watch apart from many others made in the 1940's.

Adjustment for isochronism means that the watch runs with the same rate independent of whether the watch if fully wound or almost unwound.

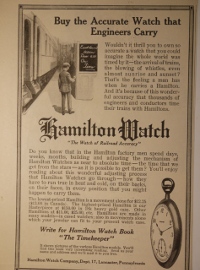

Hamilton had in the 1920's a sales and marketing brochure called the Timekeeper and it had a chapter explaining those adjustments:

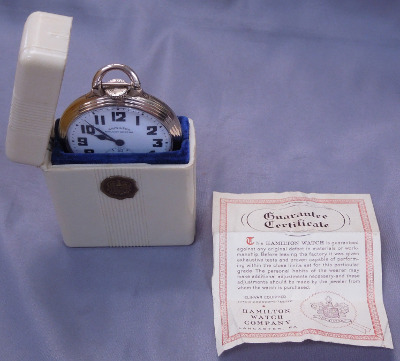

hamilton_adjustments.pdf, 238794 bytesMelamine resin (melamine formaldehyde) was one of the first widely used plastics. It's the stuff you find

on old light switches or old electrical sockets. It's a very hard and brittle

plastic. It does not easily burn and is very resistant to chemicals. The melamine resin dials do usually have cracks and hairlines after a few decades. The enamel dials may get hairlines too but generally not as big ones as the melamine dials. I have seen some cases where people have removed the original melamine and completely re-painted the dial. It looks nice but it is not original and Hamilton did not use such "paint on brass" dials for the 992b.

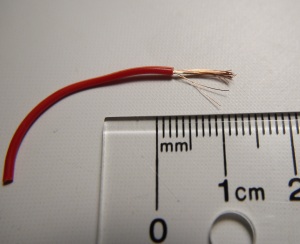

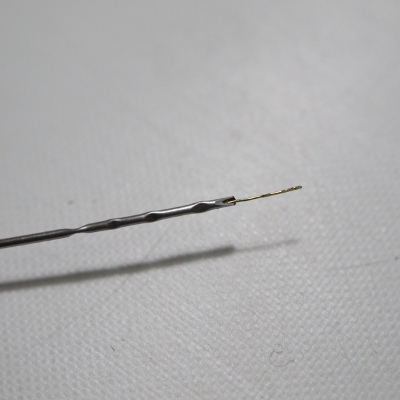

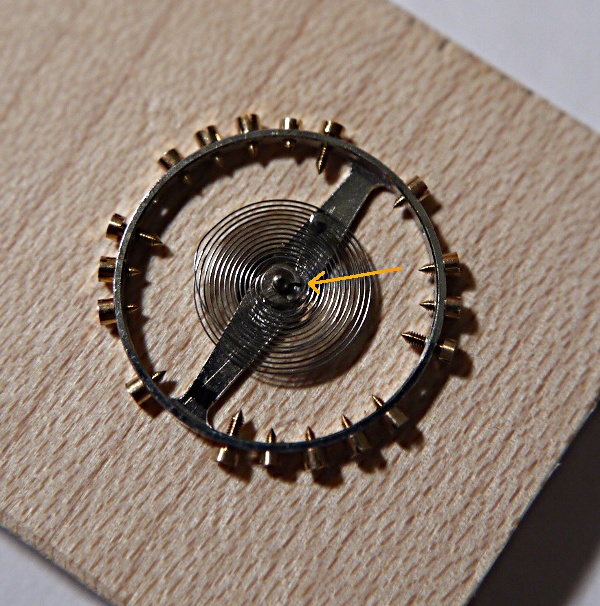

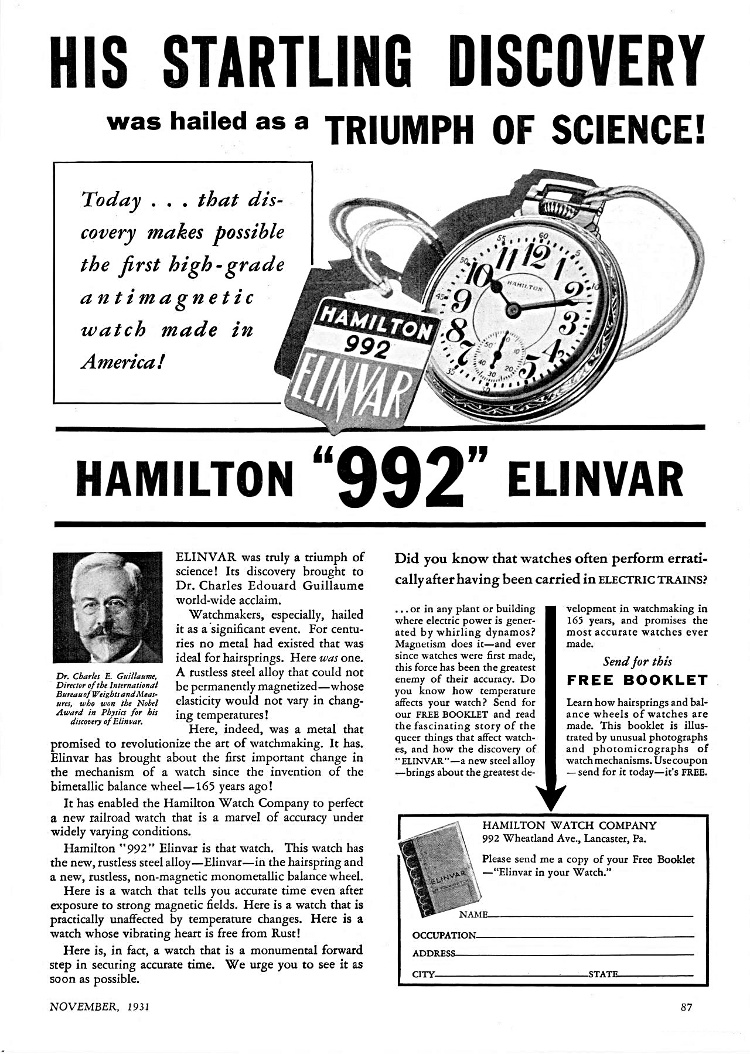

Hamilton realized that it could not continue with the Swiss Elinvar and

set out to develop a better hairspring alloy that would offer the the

advantages of Elinvar without its disadvantages. They found

the answer at International Nickel in the form of a product called

Ni-Span-C. Hamilton obtained the rights to manufacture the alloy for use

in hairsprings and it was first used in the new "B" series

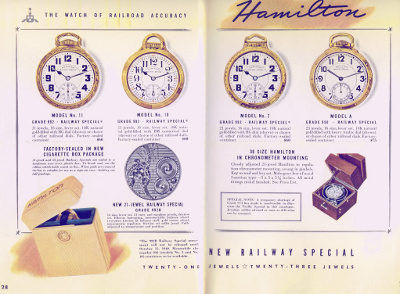

of watches that Hamilton introduced in 1940 (992B, 950B).

Ni-Span-C has a constant modulus of elasticity at temperatures from

-45°C to 65°C.

The new

alloy was called "Elinvar Extra" (Fe 48%, Ni 43%, Cr 5%, Ti 2.75%, Si 0.5%, Co 0.35%, Al 0.3%, C 0.04%). The name "Elinvar Extra" was probably chosen because Hamilton had invested

so heavily in promoting the Swiss Elinvar that they wanted the word Elinvar in the new metal. This Elinvar Extra was indeed superior and the 992B (and other B-series watches) where the most accurate watches at the time.

Hamilton realized that it could not continue with the Swiss Elinvar and

set out to develop a better hairspring alloy that would offer the the

advantages of Elinvar without its disadvantages. They found

the answer at International Nickel in the form of a product called

Ni-Span-C. Hamilton obtained the rights to manufacture the alloy for use

in hairsprings and it was first used in the new "B" series

of watches that Hamilton introduced in 1940 (992B, 950B).

Ni-Span-C has a constant modulus of elasticity at temperatures from

-45°C to 65°C.

The new

alloy was called "Elinvar Extra" (Fe 48%, Ni 43%, Cr 5%, Ti 2.75%, Si 0.5%, Co 0.35%, Al 0.3%, C 0.04%). The name "Elinvar Extra" was probably chosen because Hamilton had invested

so heavily in promoting the Swiss Elinvar that they wanted the word Elinvar in the new metal. This Elinvar Extra was indeed superior and the 992B (and other B-series watches) where the most accurate watches at the time.